Not a Fragment of the Imagination: Federal Circuit Decides in Favor of Antibody Patent Owner in Hemlibra® Dispute

Overview

On August 27, 2020, the Federal Circuit vacated the district court’s determination that Genentech’s Hemlibra® (emicizumab-kxwh) product for treating hemophilia did not infringe Baxalta’s US Patent No. 7,033,590 (the ‘590 patent) because it found the lower court had erred in its claim construction of “antibody” and “antibody fragment.”

Background and Issue Presented

Hemophilia is a rare blood clotting disorder characterized by an underlying malfunction in the coagulation cascade. A critical step in the cascade is the formation of a complex between activated factor IX (FIXa) and activated factor VIII (FVIIIa) which then goes on to activate factor X (FX). Hemophilia develops when this complex is unable to form, due in many cases to the development of self-antibodies that inhibit FVIIIa, thereby blocking the activation of FX. The disclosed and claimed invention in the ‘590 patent relates to antibodies against FIXa that take the place of FVIIIa and result in the activation of factor X by FIXa even in the absence of FVIIIa. Thus, rapid blood coagulation may be achieved in hemophiliacs with FVIIIa inhibitors by administering the claimed anti-FIXa antibodies.

Claim 1 of the ‘590 patent is illustrative.

- An isolated antibody or antibody fragment thereof that binds Factor IX or Factor IXa and increases the procoagulant activity of Factor IXa.

Baxalta filed suit against Genentech claiming that Genentech’s Hemlibra® (emicizumab-kxwh) product “indicated for routine prophylaxis to prevent or reduce the frequency of bleeding episodes in adult and pediatric patients ages newborn and older with hemophilia A with or without factor VIII inhibitors” infringed Baxalta’s ‘590 patent. Hemlibra® is a humanized bispecific monoclonal antibody that mimics FVIIIa “by bridging FIXa and FX in a manner similar to FVIIIa,” thereby allowing the coagulation cascade to continue even in the presence of FVIIIa inhibitors.

The district court found that Hemlibra® did not infringe the claims of the ‘590 patent based on its claim construction that the terms “antibody” and “antibody fragment” excluded bispecific antibodies, such as emicizumab-kxwh.

Thus, the issue on appeal was whether the district court erred in its claim construction of these terms.

District Court’s Construction of “Antibody” and “Antibody Fragment”

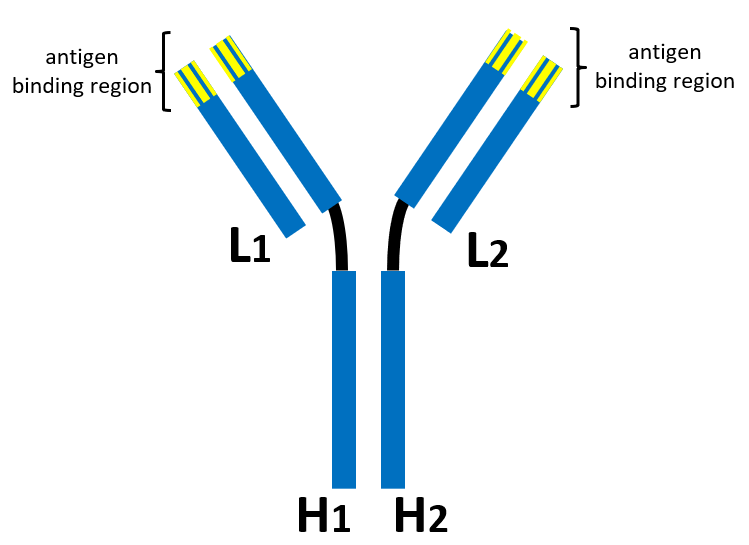

The parties disputed the meanings of these terms in the lower court. A typical antibody is shown below having two light chains (L1 and L2) and two heavy chains (H1 and H2). The tops of each arm of the “Y-shaped” structure provide the antigen binding regions.

Baxalta argued that the term “antibody” should broadly mean “a molecule having a specific amino acid sequence comprising two heavy chains (H chains) and two light chains (L chains).” On the other hand, Genentech favored a more narrow construction whereby “antibody” should mean “an immunoglobulin molecule, having a specific amino acid sequence that only binds to the antigen that induced its synthesis or very similar antigens, consisting of two identical heavy chains (H chains) and two identical light chains (L chains),” which, according to Genentech, reflects Baxalta’s patent specification and would exclude bispecific antibodies.

The district court admitted that both proposed constructions were acceptable in the art but favored Genentech’s construction because it is precisely how Baxalta defined the term in its own patent specification. The district court further recognized that while Baxalta’s patent described and claimed bispecific antibodies, it regarded these as “antibody derivatives” as they “do not have identical heavy and light chains.” Therefore, the district court adopted Genentech’s construction of an “antibody” as “an immunoglobulin molecule, having a specific amino acid sequence that only binds to the antigen that induced its synthesis or very similar antigens, consisting of two identical heavy chains (H chains) and two identical light chains (L chains).”

In reaching its claim construction, the district court relied on the prosecution record of the ‘560 patent, noting that in response to an enablement rejection, Baxalta amended the term “antibody derivative” to “antibody fragment,” thereby disclaiming antibody derivatives that included “bispecific antibodies…”

The district court then went on to also construe “antibody fragments” as “a fragment of an antibody which partially or completely lacks the constant region; the term ‘antibody fragment’ excludes bispecific antibodies.”

The parties stipulated to non-infringement based on the district court’s final claim construction and Baxalta appealed, contending that the lower court’s claims constructions were wrong.

The Federal Circuit’s Decision

The Federal Circuit agreed with Baxalta, holding that the lower court’s claim constructions were erroneous. The district court’s decision of non-infringement was vacated and the case was remanded to the lower court for further proceedings based on the correct construction of the disputed terms of “antibody” and “antibody fragment.”

The court first pointed to the axiom that “[t]he words of a claim are generally given their ordinary and customary meaning as understood by a person of ordinary skill in the art when read in the context of the specification and prosecution history,” citing to Thorner v. Sony Comput. Entm’t Am. LLC, 669 F.3d 1362, 1365 (Fed. Cir. 2012).

To conduct its analysis, the court examined the language of the claims themselves, the specification, and the prosecution record.

With respect to the claims, the Federal Circuit first noted in connection with claim 1 that “nothing in the plain language of claim 1 limits the term ‘antibody’ to a specific antibody consisting of two identical heavy chains and two identical light chains or an antibody that only binds the antigen that induced its synthesis or very similar antigens.” The court also inspected the dependent claims, which define the “antibodies or antibody fragments” of claim 1 as a “chimeric antibody, a humanized antibody,…[and] a bispecific antibody.” The court noted each of these sub-classes of antibodies fall outside of the scope of the district court’s construction of “antibody” and that adopting the lower court’s construction would render the dependent claims reciting these terms as meaningless and invalid. The court stated that “[t]he plain language of these dependent claims weighs heavily in favor of adopting Baxalta’s broader claim construction.”

Regarding the specification, the Federal Circuit held that the specification when read as a whole also supported Baxalta’s broader claim construction. Genentech’s narrower claim construction was based on a single, isolated paragraph at column 5 of the specification of the ‘560 patent. However, the court noted that it must “consider the specification as a whole and read all portions of the written description, if possible, in a manner that renders the patent internally consistent.” The court noted that beyond the paragraph cited by Genentech, the specification through “provides specific disclosures regarding bispecific, chimeric, and humanized antibodies…all of which do not comport with the district court’s construction.” Also, the Federal Circuit examined the language in the paragraph at column 5 and determined that it merely amounted to a “generalized introduction” and was not intended as a definitive definition of the term “antibody.” The court also noted that it would need to invalidate certain dependent claims reciting bispecific antibodies were it to accept the district court’s construction.

With respect to the prosecution record, the Federal Circuit held that it did not confirm or support the district court’s claim construction. In particular, the court did not agree that Baxalta’s amendment which changed the term “antibody derivative” to “antibody fragment” to address an enablement rejection somehow amounted to a disclaimer of antibody derivatives, including bispecifics. The Federal Circuit reasoned that there were “no clear statements in the prosecution history regarding what scope, if any, was given up when the patentee substituted ‘antibody fragment’ for ‘antibody derivative.’” Citing to precedent in 3M Innovative Properties Col. V. Tredegar Corp., 725 F3d 1315, 1325 (Fed. Cir. 2013), the court noted that in order for a “disclaimer to attach, the disavowal must be both clear and unmistakable.” The court noted multiple instances of interchangeable use of the terms “fragments” and “derivatives” and held that the prosecution record “does not clearly establish disclaimer.”

Based on its review of the plain language of the claims, the specification read as a whole, and the prosecution record, the Federal Circuit held that “the district court erred in selecting the narrower construction [of the term “antibody”], which is inconsistent with the written description and the plain language of the claims.” The court also rejected the lower court’s construction of “antibody fragment” based on the district court’s narrow read of certain excerpts of the specification, in favor of simply relying on the “plain and ordinary meaning in light of the written description as a whole.” Thus, the court construed “antibody fragment” as “a portion of an antibody.”

Takeaways:

- When drafting patent applications, consider avoiding definitions which are overly narrow, particularly where the state of the art might recognize more than one appropriate definition (as the district court noted is the case for the term “antibody”).

- Consider avoiding definitions of well-known technical terms altogether. This may allow more flexibility with claim construction. In other words, consider avoiding narrowing the meaning of well-known terms that already have a clear “ordinary and customary meaning as understood by a person of ordinary skill in the art when read in the context of the specification and prosecution history.”

- When developing claim constructions of one or more terms, avoid constructions that would render dependent claims meaningless and/or invalid.